This post is part of an ongoing blog series examining “Sure Things” (predictions that are almost guaranteed to happen) and “Long Shots” (predictions that are less likely to happen) in cybersecurity in 2017.

Here’s what we see coming on the threat landscape in 2017:

Sure Things

The ransomware business model moves to new platforms

As we highlighted in our May report, ransomware is not a malware problem, it’s a criminal business model. Malware is typically the mechanism by which attackers hold systems for ransom, but it is simply a means to an end. As noted in our report, the ransomware business model requires an attacker to successfully perform five tasks:

- Take control of a system or device.This may be a single computer, mobile phone, or any other system capable of running software.

- Prevent the owner from accessing it.This may happen through encryption, lockout screens, or even simple scare tactics, as described later in this report.

- Alert the owner that the device has been held for ransom, indicating the method and amount to be paid.While this step may appear obvious, one must remember that the attackers and the victims often speak different languages, live in different parts of the world, and have very different technical capabilities.

- Accept payment from the device owner.If the attacker cannot receive a payment, and, most importantly, receive the payment without becoming a target for law enforcement, the first three steps are wasted.

- Return full access to the device owner after payment has been received. While an attacker may have short-lived success with accepting payments and not returning access to devices, in time this will destroy the effectiveness of the scheme.Nobody pays a ransom when they don’t believe their valuables will be returned.

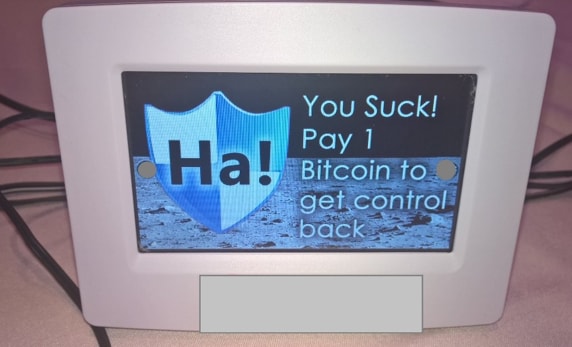

The ransomware business model can target any device, system, or data, where someone can perform all five of these tasks. At DEFCON 24 in August 2016, researchers from Pen Test Partners demonstrated taking over an Internet-connected thermostat and locking its controls before displaying a ransom note (Figure 1) demanding one Bitcoin in payment.

Figure 1: Ransom note displayed on Internet-connected thermostat at DEFCON 24

While this was not a live attack, a similar screen is sure to appear on an Internet-connected device in 2017. For a cybercriminal, making money is the name of the game. If they can capture control of a device, it’s only truly valuable if they can monetise that control. If they take control of an Internet-connected refrigerator, they will probably struggle to find data they can sell or otherwise turn into cash, but holding the refrigerator for a small ransom could be very profitable. The same is true for nearly any Internet-connected device, as long as they can complete all five tasks outlined above. It would be hard to communicate a ransom note via an Internet-connected lightbulb, unless the victim is fairly conversant in Morse code.

Political Leaks are the New Normal

Looking back on the headlines of 2016, it’s apparent that data leaks of a political nature had a significant impact in the United States. While the election may be over, I predict that these types of breaches will continue well into the future, and throughout the world.

Some features of politically focused data leaks are both desirable to government actors and dangerous for an electorate. Consider the following:

- Years of releases from WikiLeaks and others have conditioned the public to assume that leaked information is true by default. While previously released data may be authentic, this assumption could be easily exploited by a leaker interested in influencing voters.

- If leaked data has been altered, the breached party may have no reasonable way to disprove the alteration. A digital signature on a document could prove its authenticity, but the lack of a digital signature does not prove it to be inauthentic.

- A government (or government-sponsored) organisation can release information gained through espionage under the guise of a hacktivist, absolving him or her of negative political impact. Even in cases where strong evidence suggests a government was behind the intrusion that revealed the leaked data, plausible deniability exists.

Consider a case where there are private documents describing a trade negotiation between Nation A and Nation B, which Nation C does not favour. If Nation C obtains a legitimate document describing the details of the negotiation and releases an altered version, which drastically favours Nation A; the voters in Nation C may be outraged, causing the negotiations to fail. To disprove the leak, Nations A and B would have to release the actual documents, which could also cause problems for the negotiation.

No matter your political persuasion or opinion on government transparency, it’s important to understand how certain parties can abuse the current environment. Political leaks are a form of information operations that can be conducted with great effectiveness and little chance of retribution. What we have seen in 2016 will be the new normal.

Long Shots

Secure Messaging Apps Gain Widespread Adoption in Response to Massive E-mail Leaks

If people take nothing else away from the leaks of 2016, it should probably be this:

Don’t put in an e-mail what you wouldn’t want to see on the front page of the newspaper.

This is a hard lesson to internalise, as e-mail has become asynchronous communication for most of the world (and certainly people reading these words). But it’s one we should take to heart.

There are many problems with using e-mail to transmit messages that are only intended for a specific audience. The messages often sit unencrypted once they reach their destinations. Even if they are encrypted, the sender typically doesn’t have control over the security of the recipient’s system; the recipient could decrypt the e-mail and store it in plain text or mismanage their encryption keys. In most cases, the messages are sorted, catalogued, and indexed automatically, allowing an individual with just temporary access to drudge up secrets by keyword and forward them to parts unknown.

If you are wondering if you should return to simply making phone calls when you want to share a private message, that’s not a bad idea, but take a look at any teenager’s phone when considering a technology solution. Snapchat’s killer feature is messages that automatically delete themselves after the recipient reads them. This allows users to send messages with less concern about them being shared with others. There are now many security-focused messaging systems, including Telegram, Wickr, Signal and Allo, which feature end-to-end encryption and self-deleting messages. While it’s still possible for someone to grab a screenshot of one of these messages, they are often much safer than e-mail.

Widespread adoption of these services in 2017 is still a long shot, as many users may not be comfortable making the transition from e-mail. However, those who’ve learned from widespread leaks will look for alternative ways to share their private thoughts with others.

What are your cybersecurity predictions around our threat landscape? Share your thoughts in the comments and be sure to stay tuned for the next post in this series where we’ll share predictions for network security.